The Downsview Urban Design Guidelines: Moving the needle on built form

Above: conceptual rendering showing the principles of the Downsview Urban Design Guidelines applied to an urban block.

July 21, 2025

Creating built-form guidelines for Toronto’s most ambitious development prompted an essential question: should the usual rules apply?

By Kevin Bridgman and Laurence Holland

In Toronto, like most major urban centres, architects typically direct their efforts at infill or already developed sites. It’s rare to design and develop a neighbourhood, let alone several neighbourhoods, from scratch.

For decades, the Downsview Airport lands in northern Toronto have been fenced off from the surrounding city. Once a military installation and then an airplane manufacturing hub, the 520-acre site was sold by Bombardier in 2018. The ongoing redevelopment will transform the site into a series of mixed-use neighbourhoods over the coming decades.

In 2019, KPMB, Henning Larsen, and SLA were selected to design the Downsview Framework Plan in collaboration with Urban Strategies, Inc. While this plan outlined a vision for the future districts, it stopped short of determining their built form beyond outlining high-level target densities and a commitment to mid-rise and transit-oriented development.

Later, the City of Toronto invited the Framework Plan team to contribute to the district’s urban design guidelines, partly to ensure that the Framework Plan’s vision was reflected in the final outcome. In collaboration with city staff, KPMB led the development of the guidelines governing Downsview’s built form.

This project represented a unique opportunity to develop a new built-form vernacular. The city’s planning framework is largely geared towards infill development. The Mid-Rise Guidelines, for instance, presume that you’re building along a selection of existing major streets (“Avenues,” in the parlance of the guidelines). As such, they’re crafted to respond to the constraints you find in those locations: an existing “street wall” with a prevailing height and character, or an abrupt transition to a low-rise residential neighbourhood.

Most development at the former Downsview Airport lands, however, won’t be infill on an existing street or immediately adjacent to neighbourhoods. It’s an open gray-field site, bisected by a decommissioned 2-km runway and dotted with airplane hangars and light-industrial infrastructure. While the site, effectively a ridgeline between the Don and Humber rivers, was once a gathering place for the region’s Indigenous peoples, its immediate history has been devoid of the residential conditions that much of Toronto’s planning framework typically responds to.

Accordingly, we approached the project with an overarching question: what should guide the form and scale of new buildings when the typical constraints don’t apply? Our answers centred on three interrelated ideas: compact built form, transitional typologies, and courtyard blocks.

Compact built form

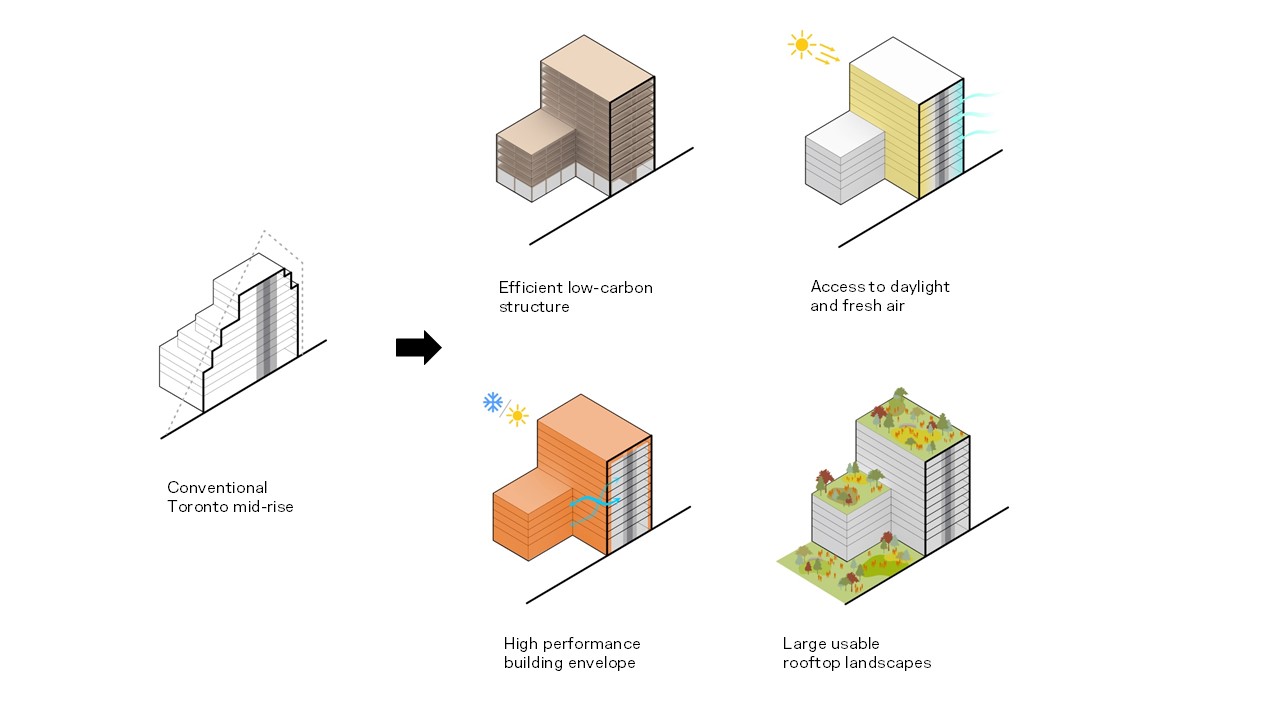

In infill contexts, Toronto’s urban design guidelines produce the now-familiar “wedding cake” mid-rise typology, whose stepped form is designed to reduce shadows on public streets and adjacent properties. But, as Half Climate Design’s embodied carbon study of Toronto’s Urban Design Guidelines outlines, wedding-cake setbacks come with a host of challenges — and insisting on them outside of Toronto’s established neighbourhoods doesn’t make much sense.

For one thing, setbacks and articulation negatively impact building performance: corners are envelope failure points and opportunities for thermal bridging and leakage. By contrast, a compact built form with fewer setbacks and corners encloses more volume with less envelope. It is inherently higher performing, more energy efficient, and lower maintenance.

Equally important, compact built form reduces barriers to delivering housing at scale, especially relevant amid Canada’s ongoing housing crisis. Designing simplified, compact built forms is one way that we can reduce the costs – in capital and carbon – of new development. Built-form articulation is expensive: it introduces structural complexity, it’s more complicated to detail and construct, and it limits the use of advanced construction techniques, such as mass timber or prefabrication, that can expedite construction and reduce embodied carbon. Compact built form can help developers cost-effectively deliver housing that meets the ever-more-ambitious requirements of the Toronto Green Standard.

Lastly, a compact built form improves livability. When planning frameworks force developers and architects to introduce articulation, they respond with deeper floor plates at a building’s base. The typical result: deep units with windowless bedrooms at grade and inefficient floorplans at the top. By contrast, a compact built form is efficient and livable. It offers repeatable units and optimal floorplate depths allowing for better access to natural light, fresh air, and views of nature.

Transitional typologies

Toronto is characterized by abrupt changes in density, with towers typically concentrated around large thoroughfares and transit nodes. These “peaks and valleys” are a product of the city’s efforts to insulate existing low-rise residential neighbourhoods from the impacts of intensification. This burdens a relatively small amount of land with a disproportionate share of population growth. At the same time, many residential neighbourhoods in the city’s downtown core are “hollowing out” — their population is shrinking, leaving them unable to sustain the public services and fine-grained retail that make for a vibrant community.

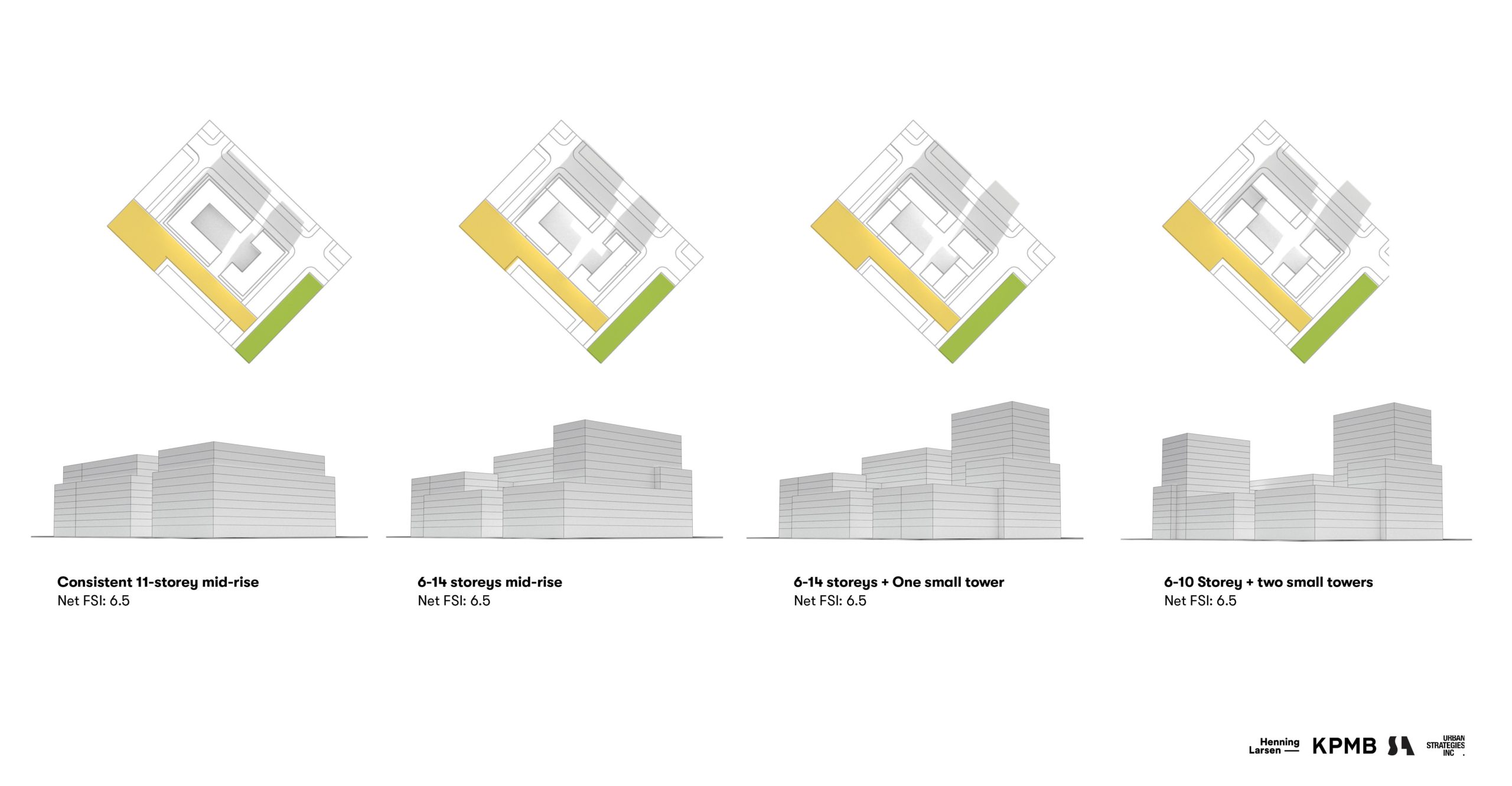

The Downsview Framework Plan determined that the area’s future districts should consist of a predominantly mid-rise urban fabric, with towers near transit stations. Under the city’s existing policy framework, however, meeting the density targets of these new neighbourhoods would necessitate filling entire district blocks with 11-storey buildings, the maximum allowable mid-rise height. This would result in a host of challenges: it would restrict built-form diversity; limit the ability of future architects to scale buildings in response to context, if needed; and yield buildings with small courtyards but extensive shadows.

Working closely with city staff, we instead defined two “transitional typologies” for the area: a “Tall Midrise” of 11-14 storeys and a “Small Tower” of 15-20 storeys. We aimed to incentivize their use by articulating bespoke guidelines for stepbacks, floor plate size, and separation distance. Deployed strategically, these typologies can carry the districts’ needed density, while letting the rest of the urban fabric be lower in average height. Such variety ultimately represents a healthier urbanism — not solely for its aesthetic variety, but because increasing and decreasing the height of individual buildings allows for expanded courtyards and improved solar exposures for the runway (envisioned as a central pedestrian and multi-modal spine) and major parks.

Courtyard blocks

In her seminal “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”, Jane Jacobs underlined the importance of short blocks as a requisite for urban vitality. Unsurprisingly, determining both the scale and form of the future districts’ blocks was a crucial part of the Urban Design Guidelines. We selected courtyard blocks to effectively balance the domestic and neighbourhood scales and establish optimal building and block sizes.

Neighbourhood porosity was a key consideration. Relatively short courtyard blocks allow for frequent mid-block connections, which — in conjunction with a web of streets, pedestrian mews, and greenways — will encourage free pedestrian movement throughout the future neighbourhoods. In this context, these courtyard blocks function as a microcosm of the larger framework plan’s network of interconnected open spaces, which help people, water, and wildlife move about the site.

Establishing the optimal building scale and layout was a second important driver. A courtyard block pushes structures to the lot perimeter, rather than filling the centre. In conjunction with compact built form principles, this creates shallower floorplates. If Canadian building codes are reformed to permit single-stair egress up to six floors, Downsview’s shallow mid-rise buildings configured around courtyards will be well positioned to deliver European-style point-access blocks with diverse, light-filled, naturally ventilated units organized around a single central stairwell.

Courtyard blocks also better support human-scaled streetscapes by reducing street widths, while simultaneously accommodating expansive interior courtyards. (The latter can house nature-based stormwater infrastructure and function as places of community-building.)

Setting a new standard for livable, low-carbon neighbourhoods

The collective vision for the future of the Downsview Airport lands is a series of low carbon, highly efficient, and abundantly livable neighbourhoods. Rigorously evaluating Toronto’s existing policy frameworks was a necessary starting point for delivering on this promise. Along with our development partners and the City of Toronto, we collaboratively questioned the relevance of such policy frameworks and developed guidelines that prioritize efficiency, livability, sustainable performance, and walkability.

These guidelines were developed in response to the unique context of the Downsview Airport lands. However, we believe their widespread adoption could positively influence development across Toronto, significantly improving our collective ability to deliver cost-effective, low-carbon, and livable housing at scale, while producing a beautiful, diverse, and high-performance public realm.

Laurence Holland is an associate at KPMB Architects. He has worked on many projects that draw on his expertise in urban design, community consultation, and multi-family residential design, along with his proficiency in policy analysis. He was a key member of the interdisciplinary Downsview Framework Plan team, working on the intersection of resilient landscapes, sustainable mobility systems, and architecture.

Kevin Bridgman is a partner at KPMB Architects, where he has contributed to the design and development of many of the studio’s most recognized projects in Canada and the United States. Kevin served as the design partner for the Downsview Framework Plan, in collaboration with Henning Larsen Architects, and SLA.