Spacing Magazine: Toronto’s missing middle should be built along collector roads, by Geoffrey Turnbull and Laurence Holland

December 13, 2019

This article was originally published in Spacing Magazine.

Much of the conversation about missing middle development in Toronto has been focused on how to smuggle additional housing units into residential areas without running afoul of NIMBY neighbours. This focus is in some ways understandable, given that the scale of building in question — somewhere between the one-to-three storey fabric of residential neighbourhoods and the six-to twelve storey midrise developments currently being encouraged along specially designated “Avenues” — isn’t covered by the city’s current planning regime.

In the absence of clear regulatory guidance, achieving a building permit for small multi-unit residential buildings has become exceedingly difficult. The situation was exacerbated in 2016 by the passage of OPA 320, which has been leveraged to prohibit small multi-unit projects in the name of preserving neighbourhoods’ “established physical character.” The result is that the early-20th-century walk-up apartment buildings that dot downtown Toronto’s residential areas would be almost impossible to build today.

Earlier this year, KPMB Architects — under the aegis of KPMB LAB, the firm’s research and innovation group — launched an initiative to advocate for missing middle development. Over the last several months, we have watched the idea of gentle densification move from the fringes to the centre of the conversation about how to solve Toronto’s housing affordability crisis. But the question remains how to deliver this kind of development.

We believe the way out of this impasse is implicit in the city’s prevailing planning logic. Just as the city has identified certain major arterial roads as good candidates for mid-rise buildings, we believe the key to encouraging true missing-middle development is finding the right scale of street.

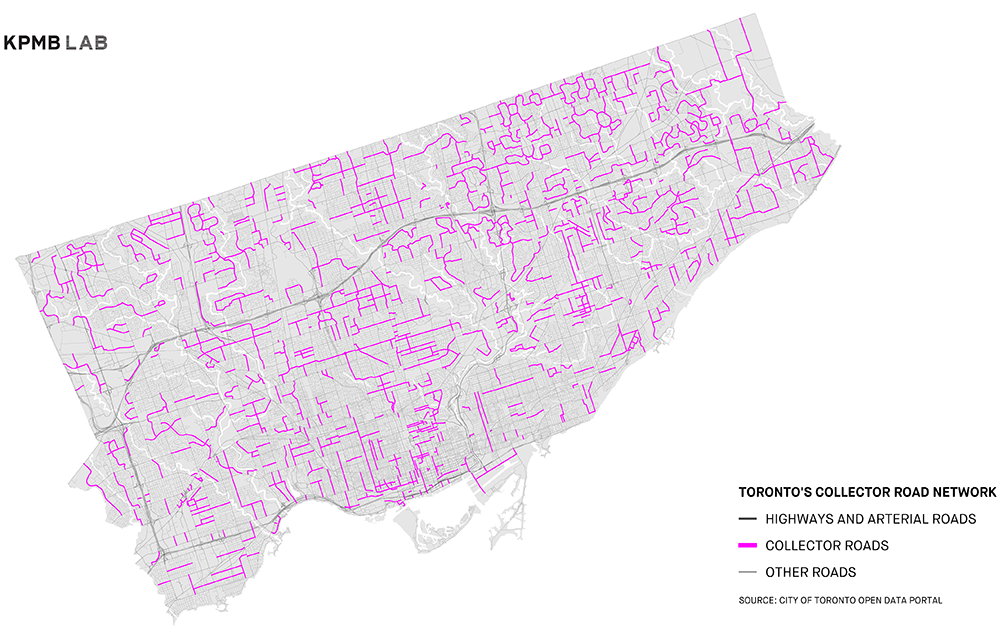

Toronto has an existing network of “collector roads”— wider than your typical local street, but not as large as the Avenues. Many run through the heart of the city’s residential neighbourhoods. We believe these streets — which include, for instance, Shaw St. and Wallace Ave., in the west end, and Logan Ave. and Sammon Ave. in the east end — represent a unique urban design opportunity.

Both on the merits and as a way of strategically building public support, we believe that the City of Toronto should start by concentrating missing-middle developments along these streets, and take a holistic approach to the design of the buildings and the streetscape. Toronto should create vibrant, pedestrian-priority corridors of local culture and commerce, sustained by a critical mass of residents in low-rise, multi-unit buildings.

Hallam Street

Creating Community Collectors

This photo shows Hallam Street, a collector road that runs from Shaw to Dufferin, just south of Dupont, in the west end. Its 20-metre right of way makes it as wide as most of Bloor St. West, though it is significantly less busy. The Harbord streetcar ran along Hallam from 1916 to 1947, making it a hub of local economic activity. At one point, there was at least one corner store at almost every intersection. (We’re relying here on Sean Marshall’s excellent blog post on Hallam Street.)

Hallam St. corner stores

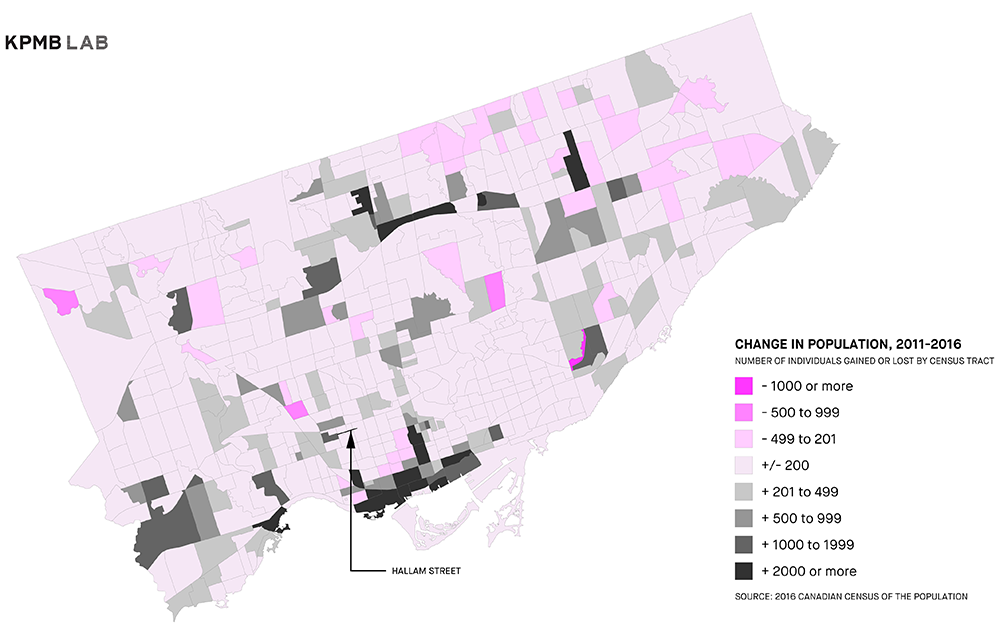

But the recent history of Hallam tells the story of Toronto’s housing affordability crisis in microcosm. With the elimination of the streetcar (the Bloor-Danforth subway line opened in 1966) and the automobile-fuelled consolidation of local retail (the Galleria Shopping Centre at Dupont and Dufferin opened in 1972), Hallam shifted towards a primarily residential use. The corner stores have almost all been converted into homes; one of them recently sold for $1.3 million. While the City of Toronto’s population has risen sharply in recent years, the neighbourhood around Hallam has seen its population stagnate.

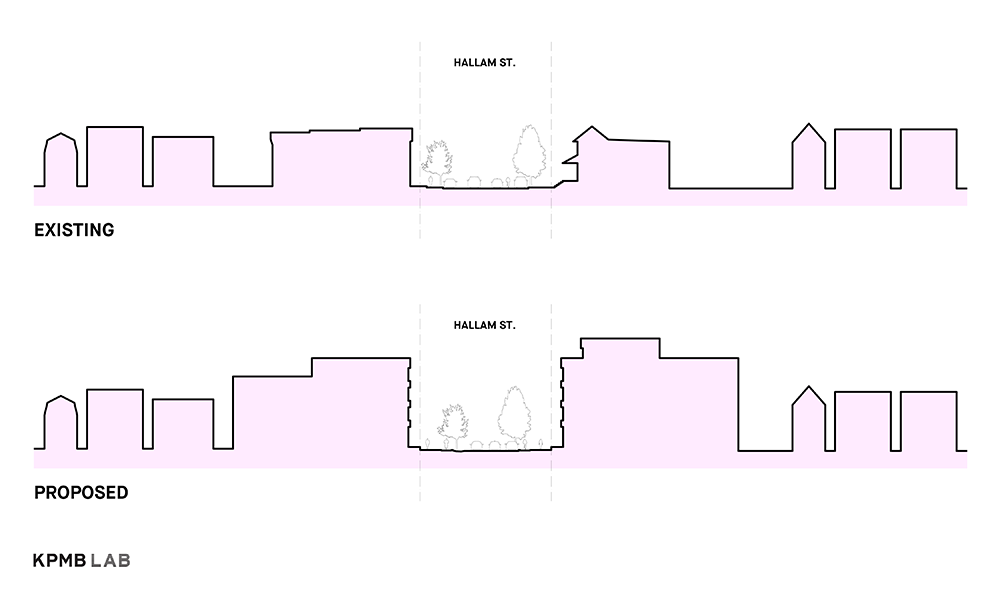

Our premise is that Hallam is a paradigmatic candidate for gentle density, in part because its width provides an opportunity to create the kind of safe, pedestrian-oriented public realm that is necessary to support a larger population, a taller street wall, and mixed-use ground floors.

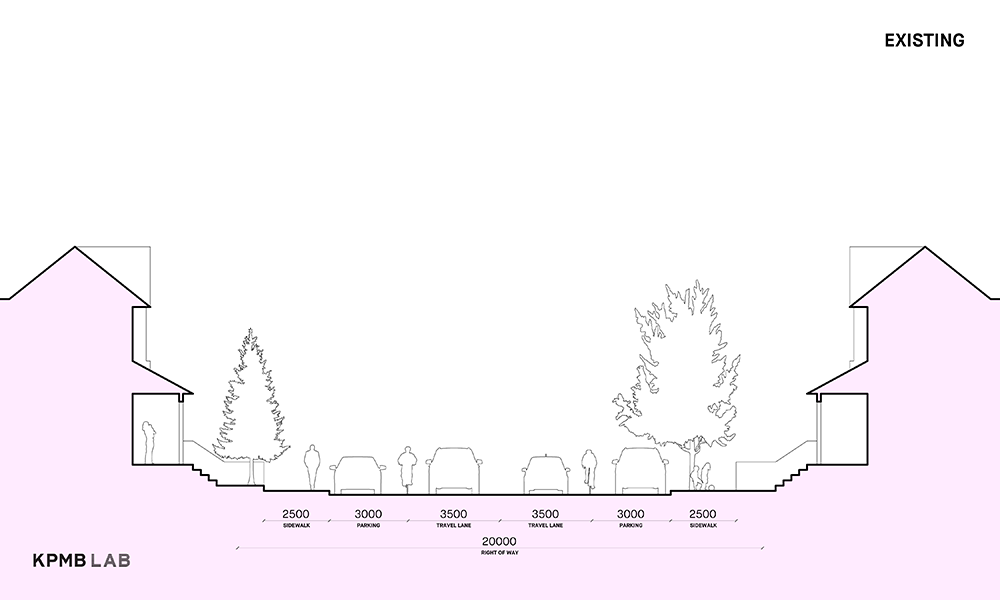

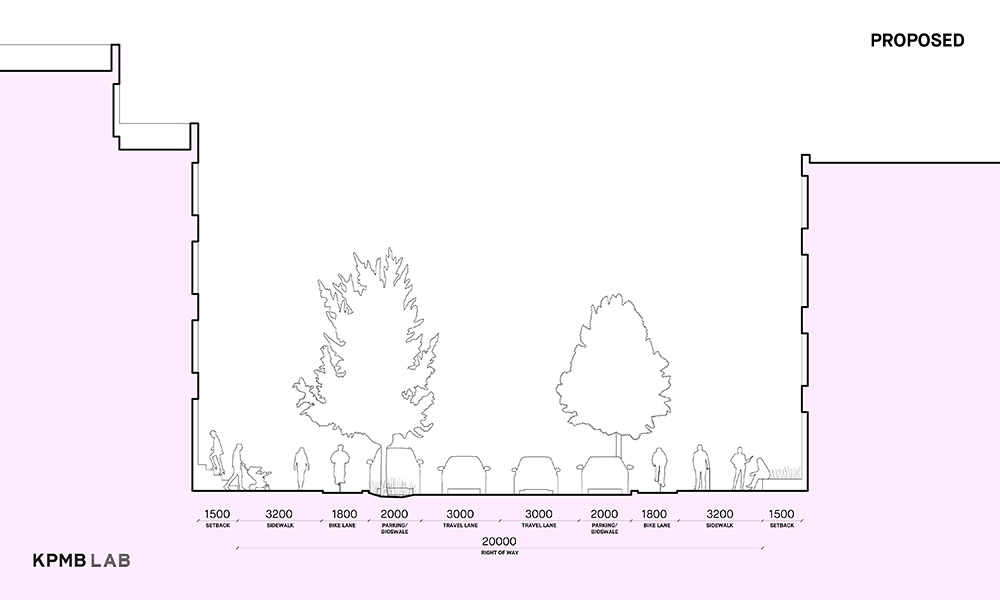

A wide, cross-section view of the existing and proposed changes to Hallam Street.

Hallam currently has two generous vehicular travel lanes, with parking on each side. There are ‘sharrows’ for cyclists, but no dedicated bicycle lanes. The sidewalks are typically around 2.5 metres wide. By narrowing the travel lanes to the city’s target width of three metres, and removing some parking spaces on each side, space can be created for two protected bike lanes, stormwater bioswales, and wider sidewalks. This is a vision of a public realm designed for people, not for the frictionless movement and storage of automobiles. Hallam Street is well-served by multiple modes of transit, with the Bloor-Danforth subway and four bus lines (including the 929 Dufferin express bus) all within walking distance. If Toronto is serious about the safety of pedestrians and cyclists, and wants to envision a new, less car-reliant future, Hallam Street would make a perfect pilot project.

There are almost 800 kilometres of collector roads in the City of Toronto. Almost by definition, they are embedded within residential neighbourhoods, connecting local roads to the arterial grid. Not all of them will be suitable for this kind of treatment, but by comparison the city has only about 350 kilometres of laneways.

By re-prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists and adding green infrastructure, the city could transform a number of these streets from collectors of vehicular traffic into collectors of community activity. Making it easy to develop four- or five-storey mixed-use buildings along these corridors would be a logical, systematic, high-impact way to increase density throughout the city while also providing the commercial, social, and mobility infrastructure needed to support that density.

Even with the increased population that comes with gentle densification, few neighbourhoods would be able to support a commercial ground floor use in every building along every collector road. There will be a mix of commercial and residential uses at grade. (Smart architectural solutions will allow easy conversion between the two.) But by increasing housing density (generating demand) and eliminating parking requirements (it’s harder to get to a huge shopping centre if you don’t have a car), the city can use community collectors to spark a revival of small-scale, walkable commerce. Cafes, restaurants, daycares, hardware stores, and corner grocers are obvious candidates. But we think that the scale and location would also be attractive to small businesses that would benefit from a storefront but don’t depend on serendipitous foot traffic. (May a thousand boutique design firms blossom!)

Supporting missing-middle developers

This proposal is an idea about an urban scale that needs more planning and design attention. We also believe the middle scale is missing in the development industry. The central challenge is the discrepancy between the ambitions of Toronto’s Official Plan and the constraints of its zoning by-laws. Instead of straightforward approvals of as-of-right building forms and densities, far too many projects involve a long negotiation with authorities over site-specific density allowances, with OPA 320 looming as a sword of Damocles.

This regulatory context introduces another layer of uncertainty into an industry that already operates with a healthy amount of risk, with two natural consequences. First, development is undertaken primarily by companies that have the political connections to navigate the process, the capital required to weather the risk, and financial backers who will lend to them despite that risk. Second, those companies focus on large projects that promise to be lucrative enough–both for themselves and for their investors–to make that risk worthwhile.

What would it take to create a cottage industry of small development companies whose business model focused on missing-middle projects? Updating the zoning by-laws to be consistent with the official plan would be a start. Giving would-be developers clarity around the amount of density allowable on a given site would eliminate a large portion of the risk associated with a missing-middle development, and make it easy for less established developers, and smaller projects, to get financing. Eliminating off-street parking requirements for developments in areas well served by transit would significantly reduce construction costs, especially for small buildings that can’t rely on economies of scale. Finally, allowing projects that achieve certain sustainability and/or affordability targets to jump to the front of the approvals queue would incentivize environmentally and socially responsible projects by substantially reducing the risk and costs associated with lengthy and uncertain approvals timelines.

The goal, ultimately, would be to create a regulatory and economic environment in which individuals or small groups felt that it was feasible to pool their resources to finance the construction of a small apartment building, either to share among themselves or for use as an investment property. A larger, more economically diverse pool of developers would build more diverse, more interesting neighbourhoods. New building typologies, innovative development models, and exciting adjacencies of use might emerge.

This sounds like a tall order, but there are international examples that we can look to for inspiration. In Melbourne, a city struggling with a similar housing affordability crisis, companies like Nightingale Housing and Assemble Communities are pioneering limited-profit co-op or rent-to-own development models that focus on sustainable six- to eight-storey mixed-use developments on small lots near transit. Toronto’s planners and politicians would do well to try to make those models possible here. Nightingale’s developments, which promise to deliver housing at up to 30% below market rates, have been wildly successful, with so much interest that units have had to be sold through lotteries. One recently announced Nightingale development is a “village” of projects that will create a critical mass of housing, retail, and public landscape. We could imagine it finding a home along any number of collector roads in Toronto.

Winning over the neighbours

Community collectors represent good sustainable urbanism. A neighbourhood with a community collector at its heart is a neighbourhood we would want to live in. A city full of them would be even better. But we believe this idea isn’t just good on the merits; it also represents a strategic opportunity to overcome one of the biggest challenges inhibiting widespread deployment of missing-middle solutions: resistance on the part of neighbouring homeowners.

Because there is no existing planning framework covering developments at this scale — and in particular because OPA 320 requires that developments in residential neighbourhoods be compatible with the “established physical character” of the area — the prevailing strategy has been to camouflage multi-unit buildings inside architectural forms that blend in with the single-family homes that surround them. (Batay-Csorba’s unbuilt “Triple Duplex” is a particularly ingenious version of this strategy.) But no matter how successful the effort, there is very little reason for neighbouring homeowners to get actively excited about such projects. Since the goal of these undertakings is to minimize resistance, the best they can hope for is to be tolerable. It is hard to imagine your average neighbourhood rate-payers’ association going to bat for them.

Missing-middle developments that help create community collectors, on the other hand, give almost everyone something to be excited about. This strategy offers a bargain: allow gentle density in your neighbourhood — not on your street, but on the street at the end of your block. In return, you may get a small independent coffee shop on your corner, and a convenience store a couple of blocks away. Your bike commute gets a little bit safer; your walk to school or to the nearest TTC station gets a little bit greener.

There are important issues that our proposal does not yet address:

- What would it take to make developments of this scale truly economically viable?

- How can the gentrifying effects of this strategy be mitigated?

- Are there ways to ensure that the apartments in these buildings are and remain affordable?

- Will this strategy make a dent in the housing affordability crisis, or is it merely a starting point?

These questions deserve thoughtful consideration. But from an urban design standpoint, we are convinced that the community collector/missing middle strategy represents a promising way forward. To build broad public support, and a better city, don’t just focus on smuggling density into residential areas. Let’s leverage missing middle development to create safe, vibrant, sustainable public spaces in the heart of Toronto’s neighbourhoods.