Advancing mass timber in healthcare architecture

September 18, 2025

Despite its transformative potential, mass timber has yet to be embraced by Canadian hospitals. Can the existing roadblocks be resolved?

By Chris McQuillan

For decades, hospital design has prioritized efficiency and low capital cost above all else. This approach has implications for the sustainable performance of hospitals and overlooks the psychological and physiological effects of the built environment and the critical role it plays in healing.

The building industry is the world’s largest source of carbon emissions, and hospitals are among its highest emitters. In Canada, our healthcare system accounts for 4.6 percent of national greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. While measures such as electrification and heat pumps are reducing operational emissions, we need a corresponding effort to address embodied emissions to reduce the overall environmental impact.

As healthcare infrastructure faces increasing pressure from all angles — aging populations, rising costs, and climate crisis — it’s imperative that we rethink how hospitals are designed and constructed. Mass timber offers a viable path forward, aligning economic, environmental, and patient priorities. Unlike concrete or steel, mass timber expedites construction, is produced with minimized consumption of fossil fuels, and has been shown to improve patient outcomes.

Despite these advantages, mass timber has not been widely adopted by healthcare, with Canadian building codes typically precluding its use in most hospital settings. Revising codes requires advocacy and momentum is still building.

What factors are currently hindering the widespread adoption of mass timber construction in hospitals — and can they be addressed?

Capital costs

In today’s market, mass timber adds 4 to 5 percent to the overall construction cost. Complicating things further: budgets for healthcare facility design typically exclude investments in operational efficacy — in this case, health outcomes — to justify innovation or improvement.

However, it’s essential that we investigate the holistic costs and benefits of mass timber. In 2024, the average annual cost of operating a hospital bed in Canada was $933,500, with an average construction cost of $4 million. Over a 50-year period, the operational costs of a hospital bed will exceed the initial capital cost by a factor of 12. Focusing solely on initial outlays offers an incomplete understanding of cost.

Decades of research in biophilic design have demonstrated that exposure to natural materials can positively impact health and well-being. Studies suggest that wood surfaces improve patient recovery and support healthcare workers in high-intensity environments ¹, with some workplace studies and post-occupancy evaluations showing that mass timber environments enjoy a 5 to 10 percent improvement in operational effectiveness. When considered in this context, the cost premium attached to mass timber is easily outweighed by long-term operational savings — such as shorter inpatient stays or greater staff efficiency — and sustainability advantages.

Further, mass timber’s current construction cost is partly driven by a lack of industry familiarity. This is likely to decrease with growing adoption. Mass timber enables the prefabrication of components, which can accelerate construction — and thereby reduce on-site labour costs — by 20 percent.

KPMB recently designed a speculative mass timber in-patient hospital unit in collaboration with British Columbia’s Provincial Health Services Authority.

Structural limitations

Despite common misconceptions, mass timber is a strong, durable, and safe building material. Third-party engineering tests have shown that mass timber, when designed correctly, is self-extinguishing in fires and maintains structural integrity.

Meeting stringent structural span requirements and achieving adequate vibration control is perhaps the most significant technical impediment facing mass timber in healthcare. The span of a typical acute care planning grid (nominally 9-metres or 30-feet) is optimized for concrete and steel systems — larger than what mass timber favours. This doesn’t mean that mass timber is inappropriate for hospitals, but that a one-size-fits-all solution is not essential.

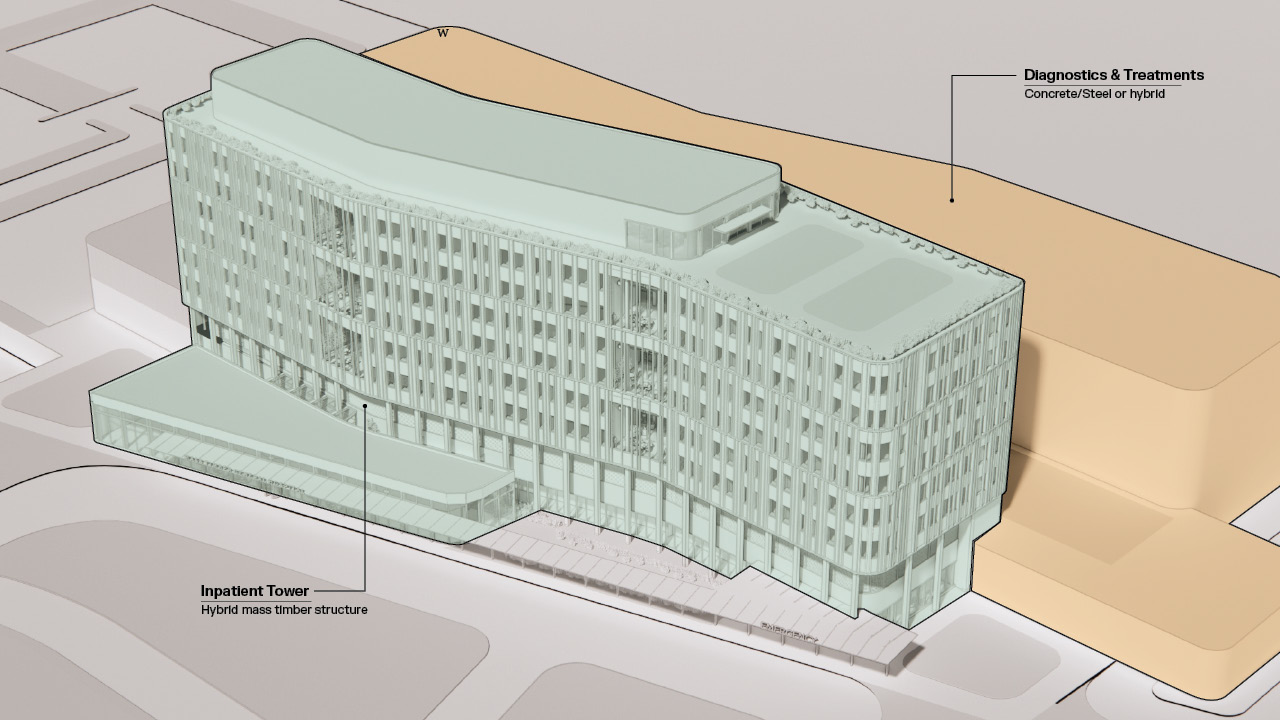

Instead, structural systems should be chosen according to the benefits they provide. Mass timber is most effectively employed in hospitals when integrated with other building systems and applied to areas where patients and staff spend considerable time and its biophilic benefits offer the greatest return. Conversely, high-criteria areas that have transient occupants and specific needs are less suited to mass timber construction. These include operating rooms with specific size requirements, sterile processing areas with strict moisture control needs, or imaging facilities with stiffness and vibration limits.

KPMB and British Columbia’s Provincial Health Services Authority — along with Fast + Epp, Smith + Andersen, CHM Code Consultants, Hanscomb, Resource Planning Group, EllisDon, and AMB Medical Equipment Planning — recently undertook a speculative mass timber study for an in-patient unit using Canadian programming and planning norms, codes, and standards. Intended as a proof-of-concept, the design addresses key structural challenges with a composite design of interior and exterior glulam mass timber columns, exterior cross-laminated timber girders, and composite steel-and-concrete interior girders. This hybrid system cost-effectively addresses vibration control and grid requirements without increasing envelope costs or inserting dropped beams that complicate service distribution — all while maximizing the benefits of exposed timber for patients and caregivers.

A hybrid approach can leverage the benefits of mass timber in areas where patients and staff spend extended time, such as inpatient units.

Infection prevention and control

Healthcare standards recommend against the use of porous, cellulose-based materials in clinical areas. Typically, exposed wood in a healthcare environment has been perceived as a sanitation risk. Wood is porous. It cracks and checks with age and can abrade and splinter with wear. Despite this, microbial and virologic studies are beginning to present a more nuanced picture of wood’s capabilities, with some emerging research suggesting that wood surfaces in healthcare settings may outperform materials that are accepted for widespread use, such as stainless steel and plastics. ² ³

Concerns also extend to potential risks regarding mass timber’s susceptibility to rot and mould. Hospitals have many wet areas and buildings will be exposed to the weather while under construction. Can this be managed? In short, yes. Comprehensive planning for moisture management during construction, environmental controls, the installation of leak detection sensors, the careful detailing of plumbing penetrations, and the use of local membranes are proven approaches.

A mass timber staff hub.

Going forward: addressing building code restrictions

Across the country, building code limitations on mass timber buildings are being re-written, largely due to market pressure from the residential and commercial sectors. Consequently, residential mass timber towers can now be built up to 18-storeys tall and with a footprint far beyond all but the largest hospitals.

From a technical perspective, and with modest alternate compliance measures, we believe that the groundwork exists to obtain approval for a B2 mass timber high-rise structure. Despite structural limitations, modest construction premiums, and concerns related to performance and durability, mass timber is an effective alternative to conventional hospital structures, especially when applied to select patient areas and used in conjunction with other building systems. It can improve patient outcomes, increase productivity, and reduce embodied carbon leading to a greener, healthier Canada.

Healthcare facilities must evolve to meet the needs of modern medicine, climate responsibility, and human-centred care. Of all the materials at our disposal, mass timber offers us the best opportunity to meet these needs head-on. What’s required now is for the marketplace to drive regulatory change.

Chris McQuillan is a principal at KPMB Architects. In collaboration with Juan Martinez of the Provincial Health Services Authority and Lisa Miller-Way of CHM Fire, Chris is developing a whitepaper about the mass timber healthcare tower study. Further details regarding its publication will be available soon.