“Bilbao on the Prairie”: Remai Modern makes international news in the The Guardian (UK)

Article content

Click here to view The Guardian

This isn’t just a gallery, it’s an act of making a city,” says Bruce Kuwabara, founding partner of KPMB Architects, at the opening of the Remai Modern, a vast glass-and-steel art museum in Saskatoon. The C$84.6m (£51m) project would be a major event for any city, let alone a small university town of 250,000 in the wheat-filled Canadian prairies.

Saskatoon is on the cusp of something. It’s the third fastest growing city in Canada, has one of the country’s youngest demographics and its economy is growing (though not as fast as it was). The latter fact is thanks in great part to an oil and gas industry that, controversially, is charged some of the lowest tax rates in the world and has helped create more than 8,000 millionaires in the province of Saskatchewan. The Remai Modern – four horizontal cantilevered volumes in a raised position by the South Saskatchewan river – is also the recipient of one of the biggest philanthropic arts donations in Canadian history.

A series of new developments are being built across the road from the museum, including an office tower, a high-rise condominium and a 15-storey boutique hotel. The downtown neighbourhood of Riversdale, a short walk away, was until recently a cheap home for new immigrants and less affluent communities. It is fast filling up with independently owned bars, artisan coffee shops, trendy co-working spaces and small restaurants serving experimental and locally grown fare.

“Riversdale was a bit of a ghost town six or seven years ago,” says Andy Yuen, owner of The Odd Couple, a independent restaurant in the area. “From a business perspective, having a world-class gallery a 10-minute walk away is amazing.”

This is not the first time a smaller city has tried to reinvent or elevate itself with a high-profile gallery – think the Mona in Hobart, the Turner in Margate or, most famous of all, the Guggenheim in Bilbao. The latter spawned a phenomenon called the “Bilbao effect”, supposed to describe the trickle-down economic benefits and rise in tourism that happens as a result of this sort of splashy arts project. But will it work in Saskatoon?

The museum is confident it will and says that the Remai will support 292 full-time jobs and contribute $34m to Saskatoon’s GDP over the first two years. Jen Budney, a Saskatoon-based curator, is more sceptical. She believes that even in Bilbao the “effect” is highly questionable: poverty has risen in the Basque city and the art scene has flourished only thanks to generous investments in grassroots arts organisations by city officials.

“Even if the projected number of tourists do arrive in Saskatoon, in the absence of any other policies and programmes, the real ‘Bilbao effect’ will be the creation of a few highly paid managerial positions and many more minimum-wage jobs,” she says.

Priscilla Settee, professor of indigenous studies at the University of Saskatchewan, believes the money for the museum could have been better used. “Poverty is a huge issue for too many Saskatoon residents, many of whom are indigenous peoples,” she says. She rues the loss of the city’s former Mendel ArtGallery – whose entire collection of 8,000 works was inherited by the Remai Modern – arguing that its free admission, seven-day opening and long hours that meant “people of little means felt it was accessible”.

The Remai Modern’s long inception and cost overruns, which had to be covered by city funds at a time of significant municipal cuts, only makes matters worse, she says.

Originally projected to cost $55m, the Remai finally came in at over $80m (or $100m if you count the car park beneath, which it shares with a local theatre). The money for construction came largely from federal, provincial and city funds – and the city council (which picked up the largest share of the $55m public bill) has come under considerable scrutiny. The museum’s seven fraught years of construction attracted negative national headlines. “Sometimes it felt like we were white-water rafting and were lucky to stay in the boat,” Kuwabara jokes.

Delays with projects of this nature aren’t uncommon. In this case, the complex L-shape of the site (the museum wraps around an existing performing arts centre), undiscovered buried foundations, late changes to the design and the difficulty of sourcing expertise in a small city all go some way to explaining the time and budget overshoot.

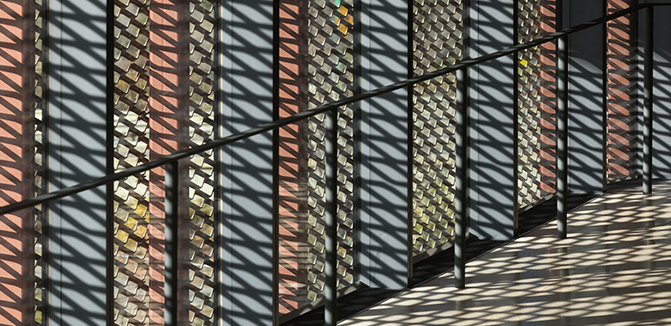

At least you can see where the money has gone. With its projecting form and copper-coloured metal screens, the building manages to look at once civic, welcoming and elegant. Inside, KPMB and Architecture49’s design is flooded with natural light and has 11 flexible gallery spaces and a 150-seat theatre. There is a free-to-enter ground floor with children’s activity area, a fireplace (which will doubtless prove a magnet in the coming chilly months), a design shop and a restaurant. The breakout and public spaces are cleverly designed to display art as well.

The costs would have been even higher had wealthy local real estate and hotel developer Ellen Remai not put $16m towards construction costs, $17m towards international programming and acquisitions and another $20m towards the museum’s 406 Picasso linocuts, the largest collection of its kind. At the museum’s opening gala, Remai announced that she would invest an extra $1m a year in art acquisitions for the next 25 years, and committed to match eligible donations up to $1m a year for the same period. That brings her contribution to $103m.

Plenty of artists in Saskatoon and beyond feel that this sort of commitment to art acquisitions is exceptional. Lori Blondeau, an indigenous artist who had a long working relationship with the Mendel, calls it “exciting”. “In Canada there aren’t any big budgets for museum acquisitions but this museum has got one so they’re pretty lucky,” says Vancouver artist Ian Wallace, whose 2011 piece At the Crosswalk IX has been acquired by the museum. “They will be able to build an amazing collection over time.”

The museum’s director, Gregory Burke, a New Zealander who was previously at Toronto’s Power Plant Gallery, has vowed to make the Remai a “leading centre for contemporary indigenous art and discourse” and speaks of “embracing the history of indigenous peoples through modern and contemporary practice”. However, Budney – who was a curator at the Mendel until 2013 and speaks for a group of artists and arts organisers who have been vocal throughout the construction – believes his words are hollow.

“How is a museum of modern art going to address the legacies of colonialism, which you see every day in the devastating economic and social inequality in our city and province, when it hasn’t yet hired any indigenous staff for permanent senior strategic or creative positions?” she asks. The Remai Modern’s opening exhibition, Field Guide, includes a collaborative installation of works selected by indigenous artists Tanya Lukin Linklater and Duane Linklater – but they were acting as one-off guest curators. Budney believes the appointment of two indigenous board members is not enough.

Lori Blondeau calls the lack of indigenous curators at the Remai “disturbing”. “Saskatchewan has been at the forefront of contemporary indigenous art in North America for close to 50 years,” she adds. “It is already a leading centre for indigenous art. The idea that the Remai will turn it into that has been disappointing and hurtful on many levels.”

But the make-or-break factor for the museum may be the number of visitors. Critics worry that projected number of 220,000 a year is unrealistic for a museum with an entrance fee of $12 in city of 250,000. The wider province of Saskatchewan only contains a little over one million people, in an area roughly the size of France. Will art fans travel repeatedly, given the lack of direct flights from major art centres such as Los Angeles and New York, and the day-long journey required to get here from parts of Canada? The long winter, when temperatures reach -40C, may not help.

With Saskatoon’s growing and diverse population, its well-established local art scene, a state-of-the-art building and the backing of a formidable patron, the Remai Modern has much going for it. But whatever happens, it will take a few years for the true “Remai effect” to become clear.

Related News

Downsview Framework Plan wins National Urban Design Award

April 17, 2024

)

)

)